Alabama Bound

Once I was walking down an alley on Music Row when Randy and Teddy stopped and invited me to listen to a new song they'd just recorded, “I'm In a Hurry.(And Don't Know Why).”

The death last week of Jeff Cook, a founding member of the band Alabama brought to mind the many encounters I've had professionally with the supergroup. I never meet Cook nor the drummer, Mark Herndon. But I spoke often with fellow founders Randy Owen and Teddy Gentry, mostly about current or impending albums. Once I was walking down an alley on Music Row when Randy and Teddy stopped and invited me to listen to a new song they'd just recorded, “I'm In a Hurry.(And Don't Know Why).” That would have been in 1992.

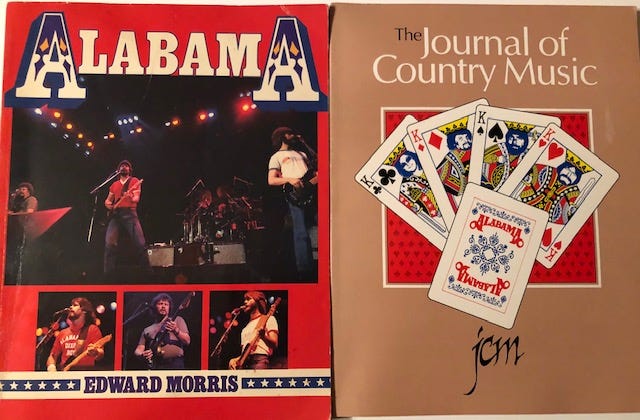

In 1985 Contemporary Books had contracted me to write a book on the group. When I told the band's management company, it let me know in no uncertain terms that I didn't have its permission—and certainly not its cooperation—for such an undertaking. But I wrote it anyway—and to no ill effects or, as far as I could tell, any hard feelings from the members. The following year, “The Journal of Country Music” had me do a cover article on the band. Thirty years later—in 2016--the Country Music Hall of Fame & Museum hired me to write the lead article for the program book for its Alabama exhibit that ran for 10 months. I took that employment to be a vote of confidence from the band, and it resulted in the essay below:

Alabama

“. . . the satisfaction of being understood”

` “Alabama!”

The sound snaps out at you like a proud declaration.

Alabama! Sweet home where the stars fell and the Tide rolls. Kissing Jim Folsom and hissing George Wallace. Dr. King’s Selma, Wernher von Braun’s Huntsville and Hank Williams’ Montgomery. Lookout Mountain and Mobile Bay. The heart of darkness and “I saw the light.” Upfront and unknowable.

This was the dizzying cultural legacy the band Wildcountry assumed as its own in 1977 when it switched its name to that of its home state. But what began as a name of convenience quickly became an irresistible artistic pull. In various guises, Alabama, the state, would forever be the creative polestar for Alabama, the band.

Randy Owen, Teddy Gentry and Jeff Cook, cousins from the hamlet of Fort Payne, Alabama, formed the Young Country band in 1969 and made their first appearance at the Bowery nightclub in Myrtle Beach in 1973. There over the next six years they refined and polished their playing, songwriting and stagecraft. Then, in 1979, after having gone through more drummers than Spinal Tap, the band hired Mark Herndon—he of the cool shades and rooster hair—and the die was cast. It was this same foursome that the Country Music Hall of Fame would welcome into membership twenty-six years later.

Harold Shedd, who produced Alabama’s first eight albums, was astounded when he first saw the band perform at the Bowery. “They were doing original songs,” he marvels. “Not only were these songs not on the radio, some of them weren’t published or even finished. And the people were just going nuts.”

From the start, Alabama had a sound distinctly different from the reigning country bands—the Statler Brothers, with their Southern gospel solidity, and the Oak Ridge Boys with their vocal pyrotechnics. Constructed around Owen’s ultra-resonant lead, Alabama’s harmonies were smoother, warmer, at times more ringing and virtually borne aloft by the sheer earnestness of the lyrics they chose.

The homeward-looking songs that launched the band’s career—“My Home’s in Alabama” and “Tennessee River”—were perfect fits for an America that had begun looking inward following the disgrace and resignation of a president and the loss of a foreign war. Such seismic turmoil made the thought of home and simple living especially appealing. Moreover, the U. S. had by this time elected a southern president who made much of his small Georgia hometown, colorful family and love of country music, all comforting gestures to these hometown kids with big ambitions.

Country music also found its audience widening and getting younger thanks to two current movies—Coal Miner’s Daughter, the Loretta Lynn story, and Urban Cowboy, the celebration of the Texas honky-tonk, Gilley’s. These films came out in 1980 within three months of each other, each accompanied by a bestselling soundtrack and neither indulging in the usual hillbilly stereotypes. Suddenly country music was hip. So when the boys from Fort Payne came barreling onto the stage, T-shirted, bearded, boisterous, rocking the crowd with their bubbling-over energy and looking like happy survivors of Spring Break few hands were raised against them but millions raised in applause.

Written by Owen and Gentry, “My Home’s in Alabama” was more than just a celebration of place. It was a manifesto as well, issued with the same pride and certainty that the Southern Agrarian literary movement out of Vanderbilt University in Nashville had demonstrated in 1930 with the publication of I’ll Take My Stand. Both statements were informed by the belief that rural life is more natural and thus superior to urban living and that Southern literature is second to none. “Well I’ll speak my Southern English just as natural as I please,” sings Alabama, “I’m in the heart of Dixie, Dixie’s in the heart of me.”

The primacy of the South has remained the backbone of Alabama’s thirty-nine-year string of hits via such memorables as “Mountain Music,” “Dixieland Delight,” “If You’re Gonna Play in Texas,” “Song of the South,” “High Cotton,” “Southern Star” “Down Home,” “When It All Goes South” and continuing all the way through 2015’s “Southern Drawl.”

If there is an element in Alabama’s music that rivals the South in lyrical esteem, it is romance. Their love songs are not songs of conquest or casual dalliances but of gratefulness for having love and anguish at having lost it. Love is transcendent and transformative in their book, not something to be flippant about. Certainly the emotional voltage of “Lady Down on Love,” “Old Flame,” “When We Make Love,” “Why Lady Why” and “Close Enough to Perfect,” to cite just a few examples, made Owen one of the two or three most romantic singers in the country canon (and no doubt increased the proportion of women in the group’s massive fan club). It also bears noting that every one of the eight Alabama singles that crossed over into the pop charts during the early ‘80s was a love song.

Shedd, who produced many of Alabama’s songs with rich instrumental backgrounds that made them sound anthemic, points out that the band became so big so fast that songwriters were willing to offer it their best songs, something that rarely happens with a new act. “Everybody wanted an Alabama cut,” he says.

Musical impact is notoriously hard to measure, but it is safe to say that after Alabama reached million-selling status there were more bands making it in country music than ever before. Among them were former pop bands Exile and Nitty Gritty Dirt Band as well such newer configurations as Restless Heart, Sawyer Brown, Highway 101, Desert Rose Band and Shenandoah.

But sometimes the impact was direct and inarguable, as when Brad Paisley tipped his hat in song to “Old Alabama” in 2011 (and scored another No. 1 for the band). Or when current stars Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, Kenny Chesney, Eli Young Band, Florida Georgia Line, Toby Keith, Trisha Yearwood, Jamey Johnson and Rascal Flatts covered the classics in the 2015 tribute album, Alabama & Friends. Clearly the band’s musical presence remains strong. It continues to draw huge crowds every time it ventures out of its uneasy retirement.

Owen and Gentry were wiser than they imagined when they wrote “My Home’s in Alabama,” for it puts its finger on why music is such a lure and siren call, such a magnificent addiction to those who undertake to live by it. “Could it be the satisfaction of being understood?” the song asks rhetorically. And the whispered answer always comes back, “Yes. That must be it.”

Good stuff, Ed.

Thanks Ed. Sharing with friends who I know enjoy your writing.